I have recently adopted a new daily practice that involves both mark-making and erasing to create a drawing. It is a two-step process: First, I make a quick automatic drawing or blind contour sketch in pencil (or more recently charcoal or crayon). Then I begin removing lines with an eraser. As with the drawing, there is no conscious aim but rather a sort of improvisation. I work intuitively, breaking up long lines, excavating curves and points of intersection, adding areas by removing boundaries. When I am done, I have a loose conglomeration of shapes that are new to me, that I wouldn't have consciously drawn, and which do not resemble known objects. The erased lines that tangled and obscured the shapes are still partly visible as shadows and depressions.

All of which got me to thinking about the use of erasure as a means of creating art. Most notorious, of course, is Rauschenberg’s “Erased de Kooning Drawing,” with its own mythology that has grown up around it – the initial request by Rauschenberg is always accompanied a bottle of Jack Daniels, the 40 erasers he used, the month of toil. It’s Freudian, it’s biblical, it’s iconoclastic; much of it is also, I’d wager, apocryphal.

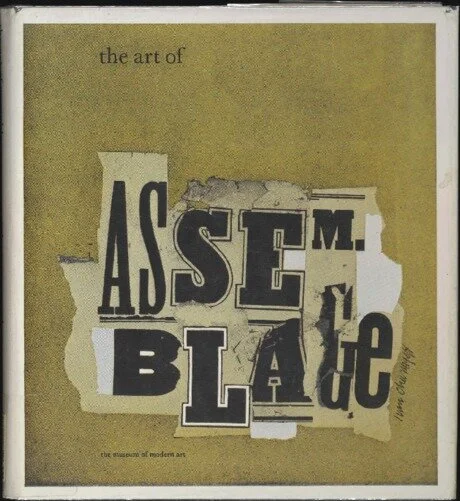

This is far from the only artist or medium employing erasure as a way of creating. Photography of course has a long history of erasure – by cropping, by dodging, by burning, and more recently by Photoshopping – that has not only artistic ends but also political and destructive ends. I am interested in the creative side of erasure, though, what Terry Winters called in a 2010 lecture “subtraction as a construction device.” Traditional sculptors, for example, use a subtractive process. Think of Michelangelo's unfinished pieces that show bodies emerging as the marble is ‘erased’. Printmaking, ceramics, collage all use removal as a means of creating.

There is another, more contemporary type of art that employs removal and erasure, usually in public spaces and within architecture, what might be called street art, though that is a poor fit in this case (one writer has termed it Intermural Art). Gordon Matta-Clark, with his Conical Intersect and Office Baroque, would be a forebear. More recently, there is Brad Downey and his excavations, such as What Lies Beneath and Searching for Something Concrete. There is a certain genealogy for Downey that one could trace that would include, in addition to Matta-Clark, artists such as Christo and Jean Claude, certain Minimalists, Joseph Beuys, Johns and Rauschenberg, straight back to the primogenitor, Duchamp. One family trait would be the puckishness that each exhibits; another, the use of what Jasper Johns called the “additive subtractive,” removing, erasing, or obscuring in order to make something new.